by Taha Boubakar

source : ncbi

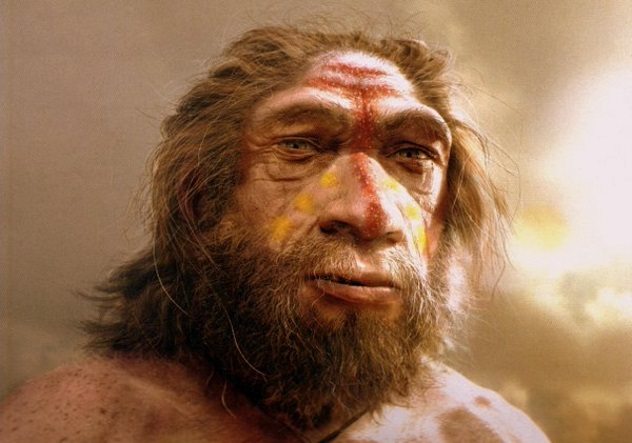

Before we talk about the scientific revolution that we have achieved in knowing our ancestors and knowledge of the genome assigned in the language and speech, We must know the nearest animal speaking to Our faction " neanderthal "

Neanderthals more rarely known as Neandertals were archaic humans that became extinct about 40,000 years ago They seem to have appeared in Europe and later expanded into Southwest, Central and Northern Asia. There, they left hundreds of stone tool assemblages. Almost all of those younger than 160,000 years are of the so-called Mousterian techno-complex, which is characterised by tools made out of stone flakes

Neanderthals are named after one of the first sites where their fossils were discovered in the 19th century in the Neandertal in Erkrath, Germany Thal is an older spelling of the German word Tal (with the same pronunciation), which means "valley" (cognate with English dale)

Neanderthal was known as the "Neanderthal cranium" or "Neanderthal skull" in anthropological literature, and the individual reconstructed on the basis of the skull was occasionally called "the Neanderthal man" The binomial name Homo neanderthalensis—extending the name "Neanderthal man" from the individual type specimen to the entire group—was first proposed by the Anglo-Irish geologist William King in 1864, although that same year King changed his mind and thought that the Neanderthal fossil was distinct enough from humans to warrant a separate genus Nevertheless, King's name had priority over the proposal put forward in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel, Homo stupidus The practice of referring to "the Neanderthals" and "a Neanderthal" emerged in the popular literature of the 1920s The German pronunciation of Neandertaler is [neˈandɐˌtʰaːlɐ] in the International Phonetic Alphabet. In British English, "Neanderthal" is pronounced with the /t/ as in German, but different vowels (IPA: /niːˈændərtɑːl/) In layman's American English, "Neanderthal" is pronounced with a /θ/ (the voiceless th as in thin) and /ɔ/ instead of the longer British /aː/ (IPA: /niːˈændərθɔːl/) although scientists typically use the /t/ as in German.

Neanderthals were shorter than modern humans, and had barrel chests, stocky limbs, and large noses—traits that were well suited to the frigid climes of Europe during the last Ice Age. Ancient DNA retrieved from the bones of two Neanderthals suggests that at least some of them had red hair and pale skin.

Neanderthals have long been depicted as powerfully built brutes that were able hunters, capable of taking down large, dangerous prey, but too primitive to have exhibited modern human behaviors. But starting in the 1950s, scientists began making a series of discoveries that have challenged the stereotype that has long plagued Neanderthals.

In 1957, anthropologists digging in Shanidar cave in northern Iraq discovered the remains of eight adults and two infant Neanderthals that appeared to have been purposefully buried some 60,000 years ago. Fossilized pollen found at the site even suggested that the dead had been buried with flowers. What’s more, some of the adult skeletons showed evidence of injuries that had been tended and healed—which suggests Neanderthals cared for their sick and wounded.

Recent findings also suggest Neanderthals used a diverse set of stone tools, controlled fire, appreciated music, and may have even communicated through song, and that they knew about the medicinal qualities of certain plants. Prehistoric art on Spanish cave walls—consisting of dots and crimson hand stencils—dating back to 41,000 years ago might also have been the work of Neanderthal artists. With so much evidence in favor of their humanity, a growing number of scientists have argued that the Neanderthals’ similarities to modern humans far outweighed any differences, which makes their disappearance all the more baffling.

Neanderthals, an archaic human species that dominated Europe until the arrival of modern humans some 45,000 years ago, possessed a critical gene known to underlie speech, according to DNA evidence retrieved from two individuals excavated from El Sidron, a cave in northern Spain.

The new evidence stems from analysis of a gene called FOXP2 which is associated with language. The human version of the gene differs at two critical points from the chimpanzee version, suggesting that these two changes have something to do with the fact that people can speak and chimps cannot.

Neandertals have the same mutations in FOXP2, the language gene, as modern humans

FOXP2 is thought to be a language gene. It is highly conserved in most mammals but in humans there are two unique mutations in the protein caused by nucleotide substitutions at positions 911 and 977 of exon 7. It is thought to be a language gene because humans who have one FOXP2 copy have speech impediments and deficiencies in orofacial movement.

Now with all the progress in sequencing the genome of Neandertals, it seems like some anthropologists and biologists from Max Planck and institutions in France and Spain got curious about finding out the whether or not Neandertals have the same two mutuations as modern humans do in their FOXP2 gene.

The new evidence stems from analysis of a gene called FOXP2 which is associated with language. The human version of the gene differs at two critical points from the chimpanzee version, suggesting that these two changes have something to do with the fact that people can speak and chimps cannot.

The genes of Neanderthals seemed to have passed into oblivion when they vanished from their last refuges in Spain and Portugal some 30,000 years ago, almost certainly driven to extinction by modern humans. But recent work by Svante Paabo, a biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, has made it clear that some Neanderthal DNA can be extracted from fossils.

Svante Paabo

Because many other genes are also involved in the faculty of speech, the new finding suggests but does not prove that Neanderthals had human-like language.

There is no reason to think Neanderthals couldn't speak like humans with respect to FOXP2, but obviously there are many other genes involved in language and speech," Dr. Paabo said.

The human version of the FOXP2 gene apparently swept through the human population before the Neanderthal and modern human lineages split apart some 350,000 years ago.

Dr. Paabo's new report pushes back the language-related changes in FOXP2 to at least 350,000 years ago, the time that the Neanderthal and modern human lineages split.

Comments

Post a Comment